Recently I see a lot of interest in making World War 1 women's uniforms and, since I am one of the few who has done so, many come to me asking me where I got mine. The answer, I am sorry to say, is that these are not available from any makers, nor are there any patterns you can buy. I have been sewing since my mother taught me at age eight and I have, in previous careers, been both a theatrical costumer, cosplayer, and historical textile conservator, so I came into World War 1 living history with the skills I needed to make almost whatever impression that I wanted. What I am presenting here is the framework of how I created my first World War 1 US Army Contract Surgeon uniform and I hope that those of you who are interested in making one such uniform yourselves may find it informative and helpful. I will be making a few post about these uniforms, since I have thus far made two: one summer cotton uniform and one winter wool one. This will deal with the summer weight version.

The finished uniform

My Summer weight uniform was based on what was, at the time, my only reference for one of the Contract Surgeons' uniforms. I have since unearthed several more, but in March and April 2018, I had what I had. Specifically, it was this uniform that belonged to Dr. Loy McAffee and now housed in the Smithsonian Institution:

Both images are from the Smithsonian's Twitter account

Since we know well that women in the Army were not issued uniforms and were therefore expected to provide their own uniforms via private purchase, I have since found that every single uniform is different according to the tastes of the wearer. This is a common basic design for a women's service uniform: male-style service coat with notched lapels, breast and hip pockets, and integrated belt. The skirt has a false buttoned front. We can also see much of the typical Army Medical Corps officer's insignia, but I will come back to that later on in this post.

Pattern Drafting

The issue, really, was creating a pattern for a uniform like this. Nothing on the market right now is correct for this style and time period, so that meant creating my own. Notched lapels are trickier than the typical mandarin collar uniform because of how closely you must control where the notches fall and and how they lie, so I did not want to start drafting my pattern from a bodice sloper as I normally would. I wanted a more solid and historically accurate base. There is a book called

The Great War: Styles and Patterns of the 1910s by R.L. Shep that reprints a number of dressmakers' diagrams from the time period. After much consideration I chose the following two:

Before you get excited, I must emphasize that these are NOT patterns. These are the basic diagrams that a dressmaker or tailor would use to draft a new pattern for each individual client. You enlarge them using the client's measurements but what you get from that is not a usable pattern, per se, because these are created for an "idealized body". The enlargements would be cut and added to and modified to achieve the correct fit. While difficult, this is achievable by a seamstress with enough experience and tenacity to keep working them until they do what you want.

For my part, I used the skirt diagram from the women's volunteer uniform and a men's style jacket diagram. The latter I chose because it is significantly less complicated to use a diagram that already has the integrated belt drafted into it than it is to add it at a later stage as I would have with the women's jacket.

Construction

I did not heavily document the construction process, since it is rarely picturesque and honestly I get so wrapped up in working that I forget to pick up the camera. If you have any specific questions, you can leave a comment here or

email me.

The textile I selected for my first uniform was a summer weight cotton twill. It is worth pointing out that cotton is harder to work than wool because wool can be "curved" a little bit over the body to create a crisper fit. Cotton does not do this so your fitting must be far more precise. I usually start with an easier piece so that I can get a feel for the fabric, which in this case was the skirt. This only really needs to fit in the waist and hips so the enlargement from the diagram did not need much adjustment.

Drawing out the final pattern on grid paper

I made my skirt entirely open down the front, which allowed me to embroider the buttonholes without fighting too much fabric. A private purchase uniform should have either hand-embroidered buttonholes or high-quality machine ones; modern machine buttonholes are not comparable. Because the buttonholes are so long, they take about forty-five minutes each to complete. Although all the buttonholes are functional, most of the front is stitched shut and only the uppermost ten or so inches were left open for the waist fastening. The skirt is lined with silk habotai, which is important so that the cotton does not stick to your stockings and other undergarments.

Left: the upper buttonhole is basted to keep the layers in place before being embroidered

Lower left and right: completed buttonholes

The finished skirt has a false buttoned front and a pleat in the back. It looks very crisp and has that nice late 1910s triangular flare. I have made a few observations about this design, however, which I will address at the end of this post.

Now, I have to say that I have only cursory tailoring expertise. It is enough, however, to know that a notched lapel needs "help" to lay the way it is meant to. In order to do this you interline the fronts of the jacket with hair canvas (I used wool) and padstitch over your hand so that the fabric gets eased a little bit into the correct curved shape. Once again, this is only partially possible with cotton, but it DID do the job it was meant to.

The method of assembling the jacket can be found in tailoring books, so I will not cover that in too much detail. My jacket is lined with silk so that it doesn't get bunched up anywhere due to friction.

Body assembled, awaiting sleeves and lining

Finished

Insignia and Buttons

With no regulations in place for what insignia female Contract Surgeons were meant to wear, I had only my own example (at the time) to work off of. Here is what we can see:

Both images from the Smithsonian Institution Twitter account

Dr. McAfee served stateside, so we can see here that on the left sleeve she wears three silver service chevrons, signifying eighteen months' service. She also wears the officers' style collar insignia: the US on her shirt collar and a Medical Corps caduceus with the CS (meaning Contract Surgeon) on her lapels. My impression, Dr. Tjomsland, served almost twenty four months, so I gave her three gold service chevrons for overseas service, as well as the officers' collar insignia, substituting a plain caduceus because I had not access to the CS version (Repros by Ray is working on one, though! Yay!). There is NO rank insignia because Contract Surgeons were only paid as first lieutenants; they did NOT receive the authority commensurate with that position.

I am somewhat interested in all the pin holes that I can see on the lapels, but we can only guess at what those may have come from.

The buttons I used on this uniform are the same as would have been used on men's uniforms, though likely hail from a later time since they lacked the black enamel. They were obtained at low cost from an antique shop and then enameled black.

Accessories

Dr. McAffee had a campaign hat, so I got one of those. I also got a Sam Browne belt for my canteen (necessary for Summer outdoors events), a maroon (Medical Corps colors) wool tie, and a wool shirt. A cotton shirt would likely be better, but finding them in small sizes AND the correct style is nearly impossible so I took what I could find. Later on I found a photo of Dr. Tjomsland in her uniform and made myself a garrison cap to match my uniform based on the one that she wore. The medical brassard was a license I took to clue people in that this is a medical impression. There are some reproduction shoes on the market, but none of them really impress me, so I wear authentic boots from the early twentieth century. I have small enough and narrow enough feet and they really do add authenticity.

It is easy to forget about undergarments, but DON'T! I wear most of the historically correct ones: a chemise and drawers and stockings. It is advisable to wear a corset, but I have yet to make one. You can get away without it but I think it would be a good addition to one's impression in terms of maintaining correct posture and body shape, as well as keeping one in the mindset of the period. So I will eventually have a corset!

Back of my uniform; unknown photographer

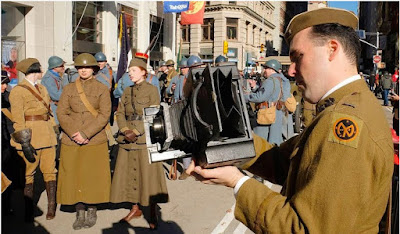

Marching in the Flag Day Parade, May 2018; photographer unknown

An authentic early twentieth century surgical gown worn over my uniform (sans jacket)

Discussion

Now that I have shown you my process and have worn this uniform for about six months' worth of events leading up the Centennial, I have a number of notes to make about it that may help any of you looking to make your own uniform. Certainly all of these points were taking into account when I made my winter uniform recently.

Point number one is that cotton wrinkles. As crisp as that pleat in the back of the skirt looks, it gets more and more wrinkled throughout the day and must be pressed again before every single event. It is not strictly necessary, so I removed it through ease and by taking in the side seams when I made the skirt for my winter uniform.

Point number two is that the pockets really need to be more functional. We all have things we need to carry and my Sam Browne belt rests right on top of my hip pocket flaps, making them VERY difficult to access. Struggling to get something out of your pockets is not a good look when you are trying to streamline your public presentation.

Point number three also has to do with the pockets and comes with an intriguing story. This summer I was part of an event in Times Square at the Father Duffy statue. A lot of top brass was there, including several generals and Cardinal Dolan. Well, a two star general came around to shake all our hands and he leaned in and asked me if I had a historically accurate phone in my pocket! Obviously the comment was made in good humor, but my next uniform got bellows pockets so that my phone and anything else I have in them is completely invisible.

Point number four is that, whether or not it is historically accurate, it is advisable to put fusible interfacing or Fray Check on any seams or hems that must be trimmed closely, such as the lapel points. I have a lot of fraying in several areas that I am not sure can be repaired. This is a modern solution to what is likely a modern problem that textiles are not as densely woven as they were in the early twentieth century.

Regardless, I may be retiring this uniform in favor of making a new summer uniform with the knowledge I gained. If I am being honest, Dr. Tjomsland wore the mandarin collar uniform and I prefer that style anyway.

My winter uniform, finished November 2018

Photographer unknown

Come back for my essay about how I made my winter wool uniform! As I said earlier on, if you have any questions, please feel free to leave me a comment or

email me.